Reconstituting Place

More and more, people rely on technology to meet their everyday needs, causing regular disruptions to real estate. However, it is worth remembering that the technology sector was itself, once the subject of its own version of disruption. What can a brief history of the emergent tech universe teach us about the future of places?

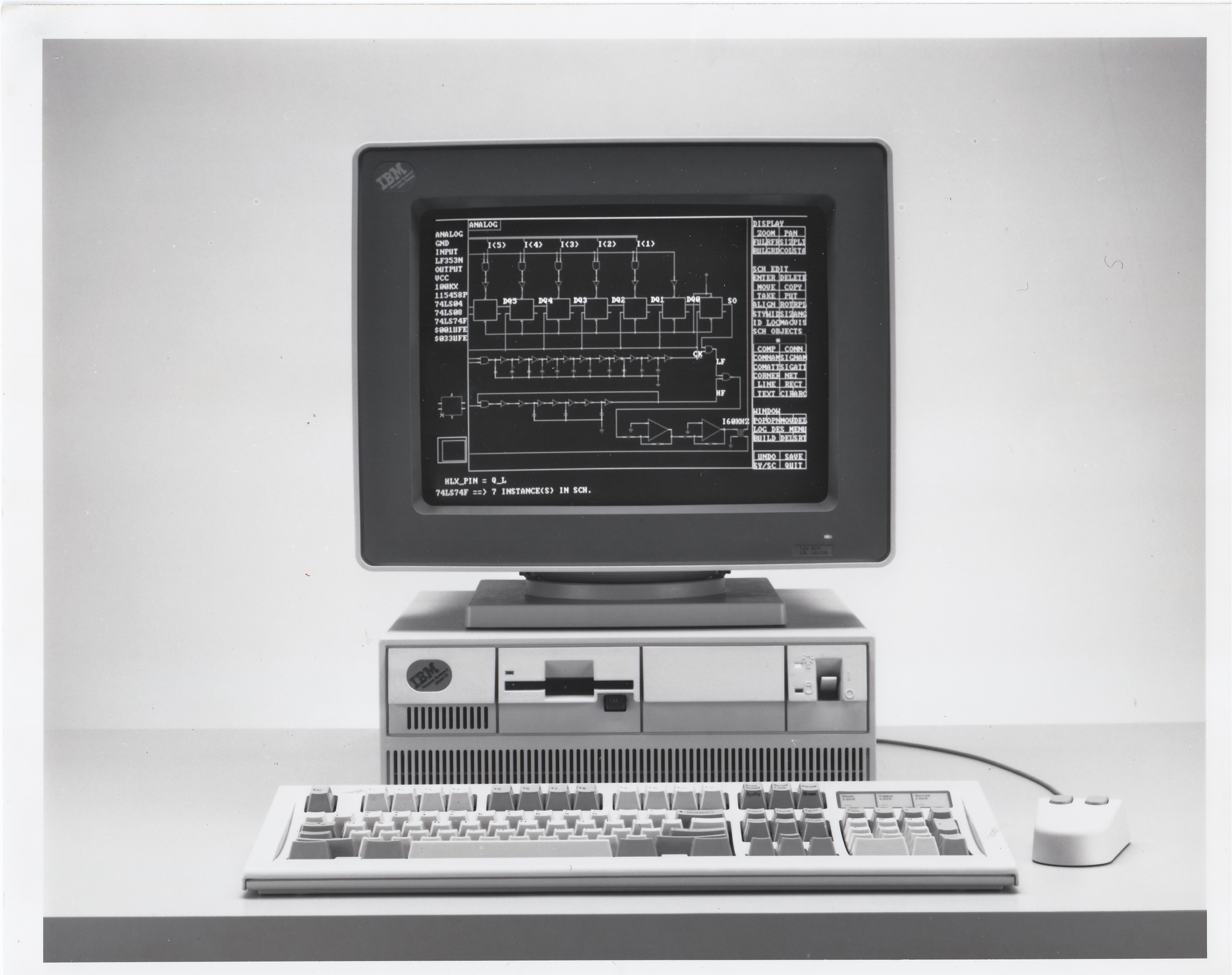

photo credit: "IBM PC" by MarkGregory007 is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

We can breathe a sigh of relief that the doomsday threat to our downtowns and urban places is wholly mis-represented. In a recent article by Richard Florida: Why Downtowns Won’t Die, he points to recent indicators showing an accelerated return to such places. Florida notes, it is a reflection of changes that were occurring before the pandemic and the purpose of urban environments will continue to change well into the future.

But, this is not business-as-usual. The story of cities may take time to fully play out, but we are already aware of deep shifts occurring. Recent changes in social behaviour, coupled with the widespread adoption of technology over time, has already created big changes in our relationship with place.

Real estate and the built environment continues to be bombarded by technological changes. The hotel and hospitality arena was forced to pivot in light of the emergence of short term lodging platforms such as AirBnB. Bricks and mortar retail is finally bouncing back but continues to be threatened by online shopping portals. Office space is the most recent to be afflicted by a move towards remote and hybrid work and the rise of online meeting platforms.

While we cannot easily predict the future, we can look at commonalities between built space and the reorganization of the technology industry to provide clues for where we may be headed.

“You don’t get points for predicting rain. You get points for building arks.”

Lou Gerstner

Remembering Giants

The story of IBM’s turnaround is well documented (Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance, by Lou Gerstner). Prior to the 1990’s, the tech universe was nowhere near as distributed as we see it today. The majority of technology products were controlled by a small base of manufacturers.

IBM was one of the originators of such technology solutions and its market share was enormous. It largely controlled the full range of available technology solutions through its vertically integrated System 360 model. However, thanks to changes in operating platforms and competition from smaller companies, by the mid 90’s IBM found its influence was dwindling. Other businesses offered IT products that customers could buy more cheaply and integrate themselves.

Unstacking the Stack

In computing terms, there is a vertical stack that encompasses all the major components of the technology ecosystem. At the bottom of the stack is hardware. Above this, sits an operating system which allows basic processes to run. Above this, there is middleware, which is a hidden transition layer. Then, towards the top of the stack you have software and applications, which people can use for various purposes, from writing recipes on a word processor to imagineering cities in Minecraft.

After their meteoric rise and then decline, IBM realized that the days of their System 360, a vertical-integration solution to the computing stack, were over. So, rather than focus on the whole stack, they looked at a growing segment – middleware. This is the hidden layer in-between, the part that glues everything together, simplifying the language between the software applications and the operating systems.

As the industry became more fragmented, middleware grew in importance. It allowed a distributed technology market to integrate its products with existing business systems. It also powered the rise of open computing platforms, networked computing and the internet. IBM, once threatened with extinction, found its new value as an integrator of IT solutions in an open, nimble way, smoothing out the complexity of systems that don’t talk to one another.

Re-modelling the Software of Place

The way we develop and operate places is becoming much more complex. There are many more players entering the arena to activate cities. Public spaces are becoming influenced more by private operators and privatized spaces are beginning to feel more civic. Attracting users, tenants and the best operators to spaces is demanding more creativity from owners. As the demand for space as a commodity dwindles and the desire for experience-centred places increases, there is a need for more creative, curated solutions.

The conditions under which many places were originally designed and the way these same places are being used and valued now are entirely different. For instance, we see buildings being repurposed to other uses to fill vacancies; properties being adapted to suit new types of tenants; rejuvenation of existing spaces where fresh market opportunities have been identified.

Even entirely new projects come across existing contexts, local communities and site interfaces that, if recognized, have abundant opportunities associated with them. All this requires a nuanced approach to redevelopment, one that can deal with the interfaces between disparate elements.

Value today is created, less by how the individual spaces function, than through their interrelationship. It’s about what happens in-between and how all the pieces of the place come together as a comprehensive whole. Handled incorrectly, it can lead to competing visions, opportunity losses and irrelevance.

Nova, Victoria, London, UK

The Place Stack

To use the computing analogy, places have a stack. Physical spaces, buildings, streets, infrastructure make up the hardware of a city. Above this is the operating system, which facilitates the user experience at its most basic level. This includes things like urban mobility, circulation systems, wayfinding and accessibility. This also involves the governance and functionality of spaces and facilities.

Then there is the software of place, where human interaction occurs. It involves how people engage with a place on an everyday level, such as through retail and business, civic and community functions, places for meeting and gathering, eating, shopping or having fun.

Latent between all of this is an underlying layer, the equivalent of middleware that is a little harder to perceive. This connects the hardware and movement systems with the experiential qualities of places. It is fluid, creating cohesion and making it easier for things to happen and for people to do things in a place.

The Missing Middleware

Our experience of cities is multifaceted and relies on the interaction of all these different components to be successful. One part of the stack relies upon others to function. When cities, buildings and places are originally conceived, we require more vertical integration to allow the systems to function, providing cohesion and compatibility between land uses and simplifying the development process to ensure buildings get built.

However, when places go through a process of adaptation or interface with an existing context, a different type of integration is required. The original creators of a place are not necessarily the same people and organizations who now operate it and continue to adapt it.

“The only constant in life is change.”

Heraclitus

Places need to develop a translation layer, mediating between existing localities and the goals of new interventions. It is the lubricant between all the distributed components of place. It is about weaving these components – new and existing, local and superimposed, into a delicate interplay that has the ability to sustain itself over time.

What does this look like exactly? There are two viewpoints to consider: top-down and ground-up. Top-down is the development’s imprint on the community. Ground-up is where the people are. To create successful places, we need to consider both the economic drivers of value for a given site and the street-level perspective.

Photo credit: Jamie Bezemer, Zoon Media

The District at Beltline (formerly IBM Corporate Park), Calgary, AB

Making an Elephant Dance Again

As part of IBM’s corporate restructuring in the 1990’s and early 2000’s, there were changes to the way the company oversaw its real estate globally. It used to own millions of square feet of space, and made the conscious decision to get out of this business in an effort to streamline operations and cut expenses.

Making up a very small part of its overall real estate portfolio was the IBM Corporate Park in Calgary, Alberta. When the decision came to sell the site and lease a much smaller footprint, the effect on IBM as a company wasn’t particularly significant. However, the legacy of the 90’s office campus continued and led to a slow decline in values, which later had a pronounced effect on the city and the local neighbourhood.

Built in the context of a rising energy sector and a vibrant economy, the IBM Corporate Park is composed of three office buildings consisting of around 400,000 sqft, within the Calgary Beltline community. Originally built to serve a major corporation, the campus design was mostly internalized and lacked any real engagement with the surroundings and its local community. The campus’s primary duty was to provide large, uninterrupted floorspace for IBM’s employees, within spitting distance of the downtown core, and still provide easy parking access for its employees.

Early Challenges

In 2019, our team of designers was asked to re-envision the existing IBM corporate park in Calgary. Within a challenged office market and high levels of vacancy, our approach was to create a new identity for the site by working within what we saw as this interstitial layer. We formed places within the place. We learned that becoming the glue between all the different pieces was vital to creating success not only in the overall design approach, but also in the project’s economics and its acceptance into the community as a whole.

At the time of the project’s renewal, owing to an economic downturn and record vacancy levels, the office leasing context in Calgary was extremely challenging. IBM’s presence on the property had dwindled and, without an anchor tenant, the campus was underperforming. What small amount of retail amenity had been active there, was no longer functional. A staff cafeteria and kitchen, remnants of a former IBM in its heyday, was unoccupied. With no ground floor tenants, the spaces between the buildings were desolate and were quickly becoming a security concern.

The new owners wanted to revitalize the former campus and create a new identity for the site. The campus needed an overhaul but also, in the context of revised demands for office space, a renewed purpose to bring people back to work.

A New Purpose

Through the redevelopment, the site became a street-to-street, active extension to the Beltline community. Now known as The District at Beltline, it incorporates new food experiences, a network of laneways and connected indoor and outdoor gathering spots at the ground level, transforming the buildings’ relationship with the site’s exterior spaces.

Boutique offices and elevator lobbies are connected to a food hall serving street food. Tenants, visitors and the local community can spill out into the adjacent laneways, courtyard and patios that are designed for year-round use and can accommodate Calgary’s winter climate. This encourages the convergence of workplace culture with spaces for socialization throughout the property’s range of third places.

Unconventional Approach

There are certain things the team to did to create success in the project that went against convention. At the start, there was plenty of vacancy, including the existing retail spaces. Yet, newly curated spaces at the ground level were proposed, including a 6,000 sqft Market Shed (now occupied by Central and 33 Acre Brewing Co.) addition with a new gastropub and microbrewery within the existing courtyard, bringing more activation and visibility to these areas.

The former staff cafeteria lacked street exposure and was deemed tough to lease. By creating a new public courtyard that would remain active throughout the year, the cafeteria space benefited from a different focus. It was quickly snapped up by a local restauranteur, Kenny Kaechele who wanted to open up a Mediterranean food concept in Kama and was keen to add to the programming of the exterior space.

Initial proposals to enclose all the outdoor space, which would have sealed it off from the exterior, were rejected in favour of creating a series of indoor-outdoor laneways and arcades. These criss-cross the property, enhancing mid-block connections and embracing the city’s cycling enthusiasts through connection to adjacent bike routes.

Photo credit: Jamie Bezemer, Zoon Media

Making an Impact

City staff, councillors and community were engaged early and quickly became advocates of the project. The project demonstrated that with the right approach and in paying attention to the street interface, gaining buy-in wouldn’t be overly difficult. This was reflected through a seamless approvals process, allowing for schedule gains and mitigating any risks associated with non-approval or changes late in the process.

The project took cues from the diversity and vibrancy of the Beltline neighbourhood by bringing in local operators and designing spaces that could be programmed year-round. The campus is quickly becoming the new nexus of Calgary’s brewing, arts and business hub. The spaces between the buildings have become a lively, growing network of meeting and mingling spots, each place with its own traits and personality to suit different moods.

Adaptation is the Future

With any place, there are diverse components that need to be carefully interwoven. Vertical integration works initially, but eventually the stack needs to be broken down and reconstituted. Creating resilient places is a continuous rebuilding process. Just as IBM created an entire infrastructure for the IT world, then broke it apart and reinvented how each of these pieces talked to one another, we need an ongoing translation for the different languages of place so they can be transformed into venues for life.

Note: IBM Canada recently announced it will open an IBM Client Innovation Centre for Western Canada, planning to create 250 new jobs in Calgary.

Will Craig is a Principal and the global chair of the Lifescape team for architecture and design firm Kasian and founder of Placeonomics.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this piece, please share it and subscribe to my newsletter.